Marathons: From Plans to Progress

Which plan should you follow for your next marathon?

I’m forever laying into reductionist coaching and sweeping claims from people of influence without them offering proper insight other than n=1. Of course case studies have value but, now that we’re spending more each on sport and physical activity than ever before (totalling $265 billion in 2022 - lol), let’s look at something we’re buying more and more of - training plans.

Training plans can be great. They’re important. However, I admit it frustrates me how I see training plans eulogised by runners and especially those providing them. They promise the world yet provide an atlas. Atlas’ are still great tools to learn from and inspire. And for many, training plans do this. Yet let’s get one thing straight, training adaptation is NOT down to the specific content outlined in a plan. It’s the complexity of the human as an adaptive system that determines if a training plan ‘works’ or not. This is a global approach, or more, this is the world, not the atlas.

Nevertheless, Autumn marathons are nearly over, and so runners and fitness enthusiasts across the globe are gearing up for months of training into spring marathons. The use, purchasing, and creation of marathon training plans are back on the rise, and on our search engines! I think now is as good a time as any, for me to go deeper…

Now, rather than rinse a magazine’s “free comprehensive marathon plan” or a popular celebrity-endorsed apps’ supposedly ‘personalised’ marathon plans for “every runner and every goal” (because then I’m no different to the source of my frustrations) we can look to some sport science research, instead. Yay for science!

A recent research paper, analysed the last 12-weeks of sub-elite marathon training plans. And not just a few - 92. This is novel, because until now, the research on marathon training has focused on what runners did to achieve a time, not what is available for us to follow.

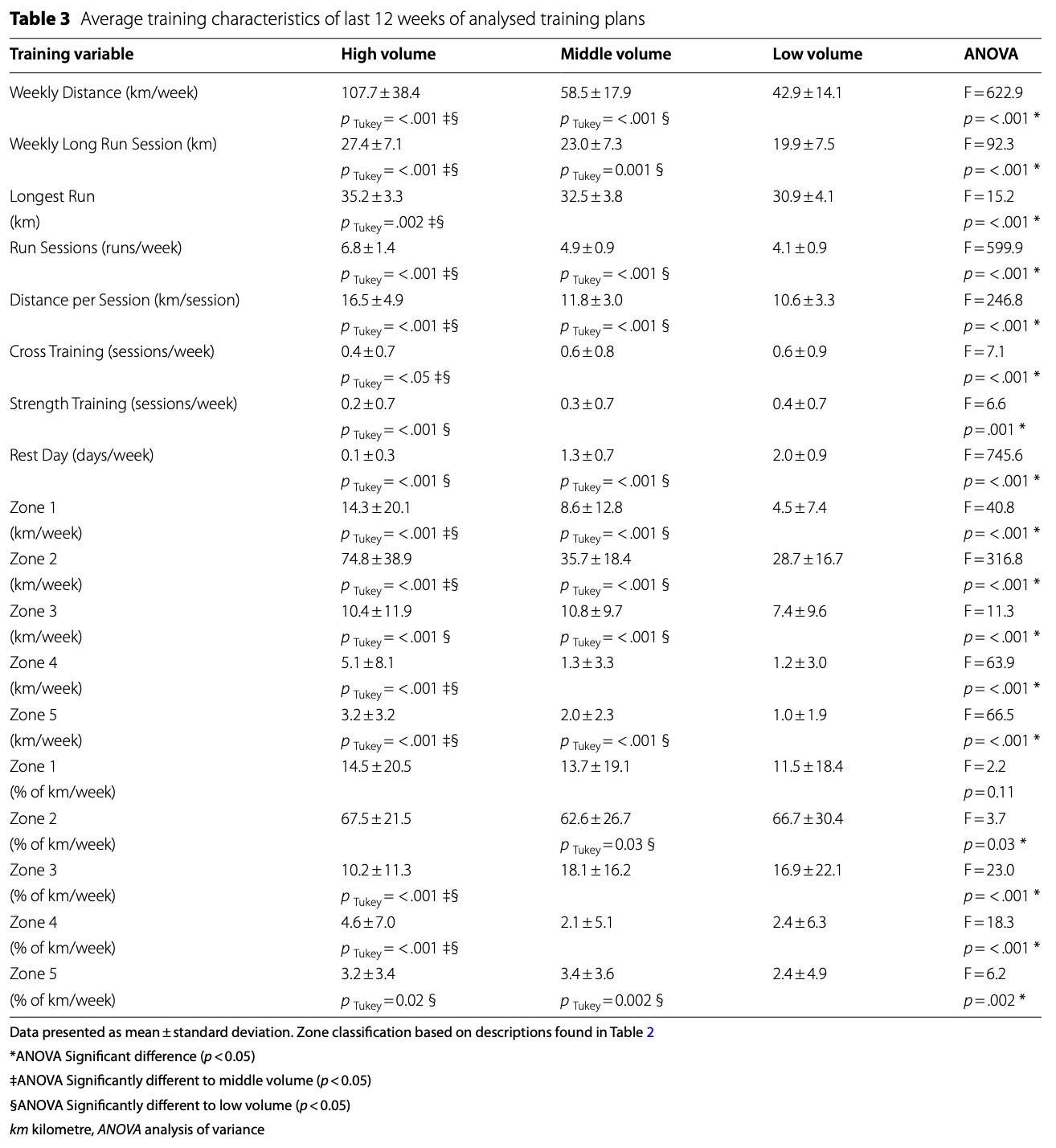

The authors simply wanted to analyse these available plans, and split them into high volume (>90km per week), medium volume (65-90km per week), and low volume (>65km per week) before analysing a few more parameters:

Weekly long run distance

Longest run in the 12-weeks

Distance covered in each session

Intensity distribution

Distance in each zone per week (5 zone model)

Percentages in each zone

Averages across the 12-week periods

Other influences such as cross-training, strength training and rest days.

One thing for me to mention is many of the featured plans have come from reputable books and sources. And also that I would LOVE to get access to that spreadsheet!!

Anyway, there’s a chance you’ll get bored if I go through the whole analysis and start watching “get ready with me” videos on Tiktok instead. So the table of results is at the bottom of this post for you to look over, and I highly recommend reading the full paper for any fellow training geeks - it’s an easy read and has some pretty graphs.

Instead, I will focus on one small result of the study, which makes a bad scientific review - I know, I know. But it caught my attention because it’s something we address in these posts and with our clients and other runners, and it leads to me making a point.

The authors found that the high, medium, and low volume plans gradually increased weekly kms, and long run volume over the final 12 weeks. “Yeah, no shit Shane - there’s a f-ing marathon at the end of it!” Anyway, the high-volume plans had the lowest rate of increase at 5% (+/- 3%) and the low-volume plans had the highest rate of increase at 9% (+/- 4%).

In numbers, it makes sense. But, remember what we keep saying with load vs capacity? Big change increases the likelihood of issues because more recovery is required to adapt to that change. This is the premise behind the research I always refer to, that training smart AND HARD, is a good thing (Gabbett, 2016). It’s why olympic athletes are olympic athletes, it’s why the ‘hybrid athlete’ has become a thing. High-volume training is all the rage, so is following a low-volume marathon training plan training still smart and hard?

Before I answer this, the authors analysed marathon training plans in an attempt to bridge the gap between science and application because studies using training plans as an intervention are tough to analyse. Unlike single intervention studies, such as taking a pill that can be tested through randomised controlled trials, training plans are complex, and human adaptation is chaotic. Marathon training evolves over time, it varies in intensity, frequency and duration, and is impacted by life. Factors such as nutrition, stress, sleep, work, kids, investments into training, social expectations, training expectations, and I could go on and on and on!

This ‘low-training phenomena’ (I just came up with that myself) does not have a binary answer. We have an insane amount of things and mechanisms going on in our lives that will have some sort of influence on how we adapt to training. And this is exactly why there is not yet, and I don’t believe there will ever be, a universal approach to training for a marathon. And, an element of natural selection can’t be overlooked. The olympians we see are where they are because have clocked up more training without set-backs killing their career progress, and why ‘hybrid athletes’ are a thing because either injured runners have had hammered strength training, or strength athletes have been able to ramp up their running volume, because they already train a lot.

I think the best we can do is learn. Try things we like the look of, but don’t be a dick about it. Understand that it’s us that adapts to the training plan, not the training plan that makes us better. This heuristic approach to training for a marathon gives you agency however you do it. Throw in loads of strength training if you enjoy it and have time. Run really high volumes if you’re body and life allows you to. But do it curiously, consciously and critically.

This is one of my favourite things about coaching. I get to work with people to offer suggestions and guidance. To talk through what it is about this particular training plan, or weekly volume, or long run, or intensity distribution that we think might work, or that has worked in the past or that hasn’t.

I do believe those who create training plans factor as much of this into their work as possible. As do I in creating the plans and frameworks behind my philosophy for adaptation to endurance training, that I’ll use in my coaching decisions.

However, today, I just wanted to highlight that a lot of plans available do vary and don’t deliver on what they promise. They are often vague, using different terminology and leave interpretation up to the reader. Because it’s just a plan. The rest is down to you.

Stay critical, stay curious, stay conscious.

Much love,

Shane

ACTIVE EDGE RECOMMENDATIONS & FURTHER READING

Main study: Knopp, M., Appelhans, D., Schönfelder, M., Seiler, S., & Wackerhage, H. (2024). Quantitative Analysis of 92 12-Week Sub-elite Marathon Training Plans. Sports Medicine-Open, 10(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-024-00717-5

Table from Knopp et al. (2004)

Gabbett, T. J. (2016). The training—injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder?. British journal of sports medicine, 50(5), 273-280. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095788